TheEpicCowOfLife's Blog

Imagine reviving this blog, couldn't be me.

Project maintained by Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Projection Algorithms 3: Sudoku (WIP)

20 Feb 2022 - TheEpicCowOfLife

In this article, we will talk about Sudoku, and why it is possibly one of the greatest denial of service attacks on the human intelligence! I’ll show how this problem can be formulated as a feasibility problem, and my various findings on how the algorithms performs.

If you haven’t read the first part, do it now, otherwise things will simply not make sense.

If you haven’t read the second part, you should do it too because it helps put everything into context.

\[\def\reals{\mathbb{R}} \newcommand{\bx}{\mathbf x} \newcommand{\bw}{\mathbf w} \newcommand{\by}{\mathbf y} \newcommand{\bz}{\mathbf z} \newcommand{\ba}{\mathbf a} \newcommand{\bv}{\mathbf v} \DeclareMathOperator{\Fix}{Fix} \newcommand{\integ}[2]{[[{#1},{#2}]]}\]Sudoku

You probably already know what sudoku is, but for avoidance of doubt, here is the problem:

You are given a 9x9 grid with some numbers filled in already. Fill in the rest of the grid such that:

- Every row forms a permutation of integers 1-9

- Every column forms a permutation of integers 1-9

- Each of the 3x3 boxes indicated by thickened borders contains a permutation of integers 1-9.

Note that a puzzle is defined by a set of filled in numbers (clues), such that there is a a single unique solution. Clearly, there are very many puzzles that exist.

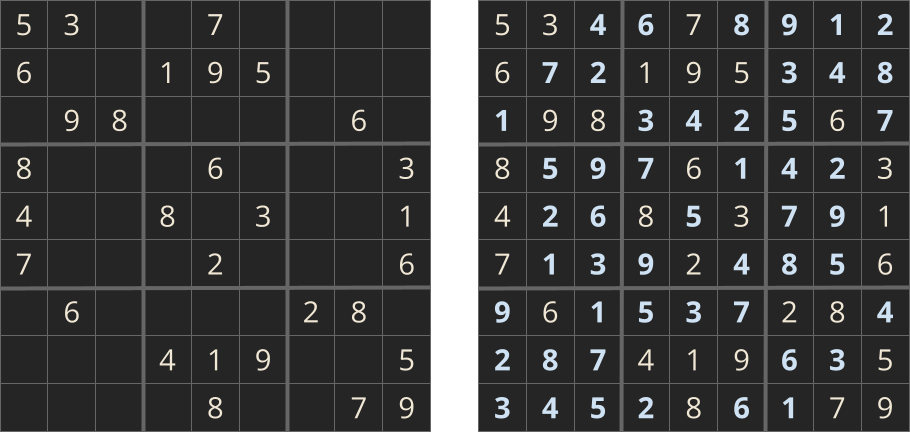

Below is an image of a sudoku puzzle, and its unique solution.

Note the following terminology:

- A cell will refer to a single space that fits a single number

- A box will refer to one of the nine 3x3 grids of cells.

In contrast to N-M queens where there can be many valid solutions, here any solution found is unique. This means that convergence of any algorithm, at all, will be quite miraculous!

The first formulation.

A first instinct is to formulate a given Sudoku board as an \(x \in \reals^{9 \times 9}\) where \(x_{ij} = k\) iff the cell at position \((i,j)\) has value \(k\).

In essence, a completed puzzle/solution \(x \in \reals^{9 \times 9}\) will have integer values between 1 and 9, satisfying the sudoku rules.

4 constraint sets can now be defined. Informally, they are:

- Each row consists of a permutation from 1-9

- Each column consists of a permutation from 1-9

- Each box consists of a permutation from 1-9

- (\(C_4\)): The board satisfies the original clues.

Clearly, the first 3 sets are just 9 copies each of the set of permutations discussed all the way back in the first part, so projection can be done quite quickly. The last set is a fairly trivial projection: to project any given \(x\) onto \(C_4\), simply change the value of any cells that have a clue to the value of the clue.

However, according to my supervisor Matthew Tam, this formulation doesn’t work very well at all, so I never tried it. I can theorise why: the labels 1-9 are arbitrary, any permutation of the clues is effectively the same puzzle! Hence, doing basic arithmetic on the labels is completely nonsense. However, the operations in Douglas Rachford and Tam-Malitsky does do arithmetic on boards. To illustrate, If a board \(A\) is confident it has a 9 at position \((i,j)\), but board B has a 1, then does the average \(\frac{A + B}{2}\) mean that \((i,j)\) has a 5? Changing a cell’s value completely could totally stuff up the puzzle!

In contrast, in an n-m queens board, if \(A\) contains a 1 at position \((i,j)\) and \(B\) contains a 0, then \(\frac{A + B}{2}\) would have a 0.5 at that position, which has a natural interpretation of now being “unsure” whether or not \((i,j)\) has a queen.

A better formulation

The formulation I implemented was as follows: Represent a Sudoku board \(x\) as \(x \in \reals^{9 \times 9 \times 9}\) where \(x_{ijk} = 1\) iff the cell at position \((i,j)\) has value \(k\), and \(0\) if it doesn’t have value \(k\).

In essence, each cell now contains 9 values each, and in a completed puzzle/solution \(x \in \reals^{9 \times 9 \times 9}\) each cell will contain exactly one 1, with the rest 0. The position of the 1 determines the cell’s value.

For avoidance of doubt, here is an onslaught of definitions. For any \(X \in \reals^{9 \times 9 \times 9}\) define the following: (Switched to using \(X\) instead of \(x\) just so the subscripting looks okay)

Reminder that the notation \(\integ{a}{b}\) denotes “The set of integers between \(a\) and \(b\) inclusive.”

\[\{X_{ij}\} := \{(X_{ij1}, X_{ij2}, \dots, X_{ij9}) \ | \ i,j \in \integ{1}{9}\}\] \[\{X_{ik}\} := \{(X_{i1k}, X_{i2k}, \dots, X_{i9k}) \ | \ i,k \in \integ{1}{9}\}\] \[\{X_{jk}\} := \{(X_{1jk}, X_{2jk}, \dots, X_{9jk}) \ | \ j,k \in \integ{1}{9}\}\]Then we also need to define \(e_i\) as the standard basis vectors in \(\reals^9\), and \(S\) as the set of all standard basis vectors as follows:

\[e_i \in \reals^9 := v \begin{cases} v_j = 1 \qquad j = i \\ v_j = 0 \qquad j \neq i \end{cases}\] \[S := \{e_i \in \reals^9 \ | \ i \in \integ{1}{9}\}\]With that in mind, 5 constraint sets can now be defined. They are:

- \(C_1 = \{X \in \reals^{9x9x9} \ \mid \ \forall v \in \{X_{ij}\}, v \in S \}\). That is, all cells consist of exactly one value.

- \(C_2 = \{X \in \reals^{9x9x9} \ \mid \ \forall v \in \{X_{ik}\}, v \in S \}\). That is, \(C_2 \cap C_1\) enforces that all rows consist of a permutation from 1 to 9.

- \(C_3 = \{X \in \reals^{9x9x9} \ \mid \ \forall v \in \{X_{jk}\}, v \in S \}\). That is, \(C_3 \cap C_1\) enforces that all columns consist of a permutation from 1 to 9.

- For \(C_4\) we can define it similarly above to enforce that \(C_4 \cap C_1\) is constraint such that all boxes consist of a permutation from 1 to 9. However trying to index everything in those 3x3 grids (in the \(i,j\) dimensions) is painful, so there is no mathematically rigorous definition here.

- \(C_5\) The board satisfies the original clues.

Projection onto \(C_1, C_2, C_3, C_4\) is easy, it simply involves many repeated projections of an \(v \in \reals^9\) onto \(S\). Using a rearrangement inequality argument similar to part one, it can be shown that projecting \(v\) onto \(S\) is as simple as setting the max value of \(v\) to 1, and the rest of the components to 0.

\(C_5\) is the same as \(C_4\) from the previous formulation, so we know how to project onto that.

Now, in contrast to the previous formulation, if a board \(A\) is confident it has a 9 at position \((i,j)\), but board \(B\) has a 1, then the average \(\frac{A + B}{2}\) will basically be perfectly undecided between a 1 and 9, with an entry of 0.5 each. This is a much more reasonable intepretation of the arithmetic done to the board.

In search of data

In contrast to nm-queens, this time we can benchmark algorithms by chucking sudoku puzzles at them and seeing how many they solve!

But where do we get good datasets of puzzle? By entering the rabbit hole.

Google was very kind to me, and I immediately found this repository. This is an extremly optimised sudoku solver, as if it was written by someone whose sole purpose in life was the write the sudoku solver to end all sudoku solvers, and end the years of man-hours spent writing sudoku solvers.

Well, it really isn’t that dramatic, but that’s what I imagined as I waded through man-years of efforts dedicated solely to the study of sudoku- scrolling down the gargantuan algorithm writeup, infinitely recursing in more and more references like some kind of horrid academic hydra. Then there was the meticulous benchmarking of a dozen top algorithms written by a dozen authors, each presumably with their own set of unique insights and observations.

Looking into the data sources, the hydra splits yet again. Not only are people solving sudokus, automating the solving of sudokus, there are people dedicating their intellect to generating puzzles? Here is a forum spanning 61 pages. Participants communicate in brief, but vague posts with code-words like “sk-loop” and “bi bi pattern”, but somehow perfectly understand each others’ dizzyingly abstract ideas: a sign of terrifying collective intelligence. They are not putting their minds to curing cancer. This is a community dedicated to writing programs to generate sudoku puzzles, with the aim for finding the hardest puzzles for computers and humans to solve.

If a denial of service attack can naturally self-replicate, does that mean that it is a virus? Is sudoku a virus?

Either way, should I be so cynical as I myself, was prepared to justify throwing my man-weeks into this black hole of intellect?

I finally took the data.zip file and left.

Inside data.zip

There were 9 data sets. I unzipped it and committed to my repository.

Foolish Quang.

There was a dataset over 100 mb when unzipped, and now I couldn’t push to github. Great. There goes an afternoon expanding my git vocabulary to try and undo some commits. If you ever run into the same situation, git reset -soft (or something like that) will undo a commit without changing the files in your repository.

After ignoring the datasets with multiple solutions or no solutions, there were 4 major data sets I considered.

- puzzles0_kaggle: 100000 puzzles, sourced from a kaggle challenge.

- puzzles2_17_clue: 49000 17-clue puzzles generated by a professor from the University of Western Australia

- puzzles3_magictour_top1465: Magictour (a mysterious online user) listed their hardest 1465 puzzles.

- puzzles6_forum_hardest_1106: The product of the aforementioned forum of people dedicating their intelligence to generating the most dastardly puzzles. These are the 375 top puzzles.

According to the tdoku repository where I sourced this data, these datasets are roughly in order of difficulty.

A Puzzle’s difficulty.

But what does difficulty really mean? Good thing reading those forums answered this question before I decided to have a crack at some of the sudokus in the dataset. Turns out people have created sudoku solvers that solve sudokus using human-like deduction. Each technique aims to make progress by ruling out possible entries from cells. They seem to work by trying to make progress by going down an increasingly esoteric list of techniques, and rate the difficulty of the puzzle by the most esoteric technique used.

What exactly are the “techniques”?

Let’s look through the dataset…

puzzles0_kaggle

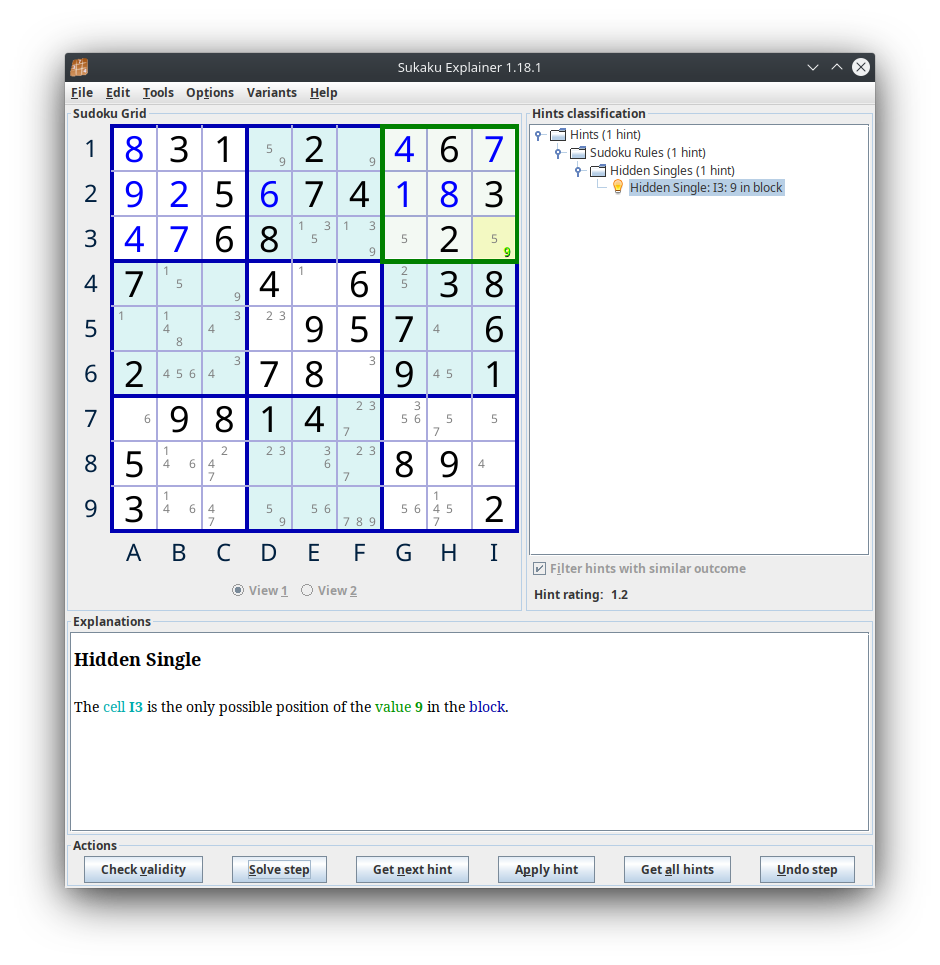

I put a couple kaggle puzzles of the dataset through and all the “puzzles” look fairly trivial: they just consist of applying the basic sudoku rules over and over like in the picture below

This is consistent with what the comments on the Kaggle post says

puzzles2_17_clue

It is well known that 17 is the minimum number of clues required for a puzzle to have a unique solution. While it may be intuitive that the less clues you give, the harder the puzzle must be, that is actually not really the case. There are some very simple 17 clue puzzles in there, that can be solved by a beginner using simple techniques like above.

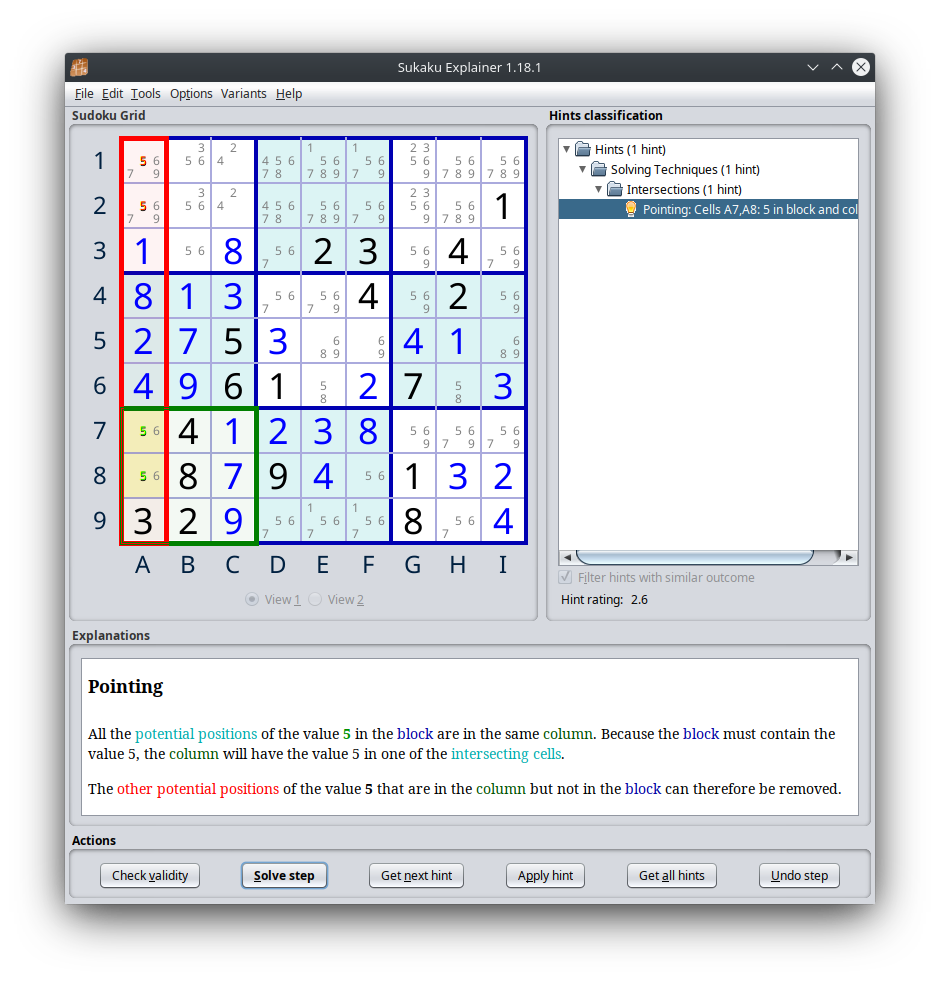

However puzzles requiring more advanced deductions are quite common in the dataset. To illustrate, here’s one such technique:

Many more esoteric technique features in the database, but an experienced human solver could reasonably do most of these.

puzzles3_magictour_top1465

Here’s where things start getting unhinged. It is at this point that people are generating sudoku puzzles with the intent of making them as difficult to solve as possible.

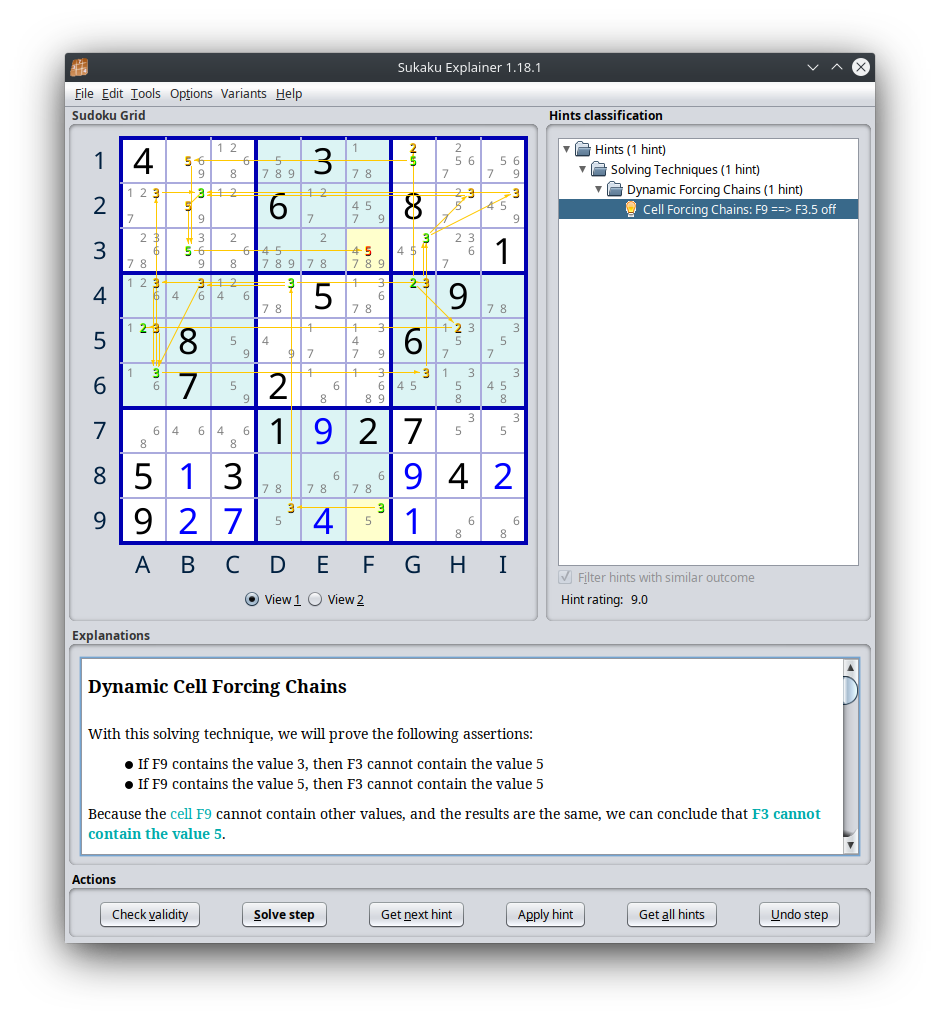

Here’s one example of a deduction required to solve the first puzzle in the dataset.

To give you an idea of what is going on in this madness, I’ve pasted the entire deduction below. Happy scrolling.

Click to show the full deduction

Dynamic Cell Forcing Chains

With this solving technique, we will prove the following assertions:

If F9 contains the value 3, then F3 cannot contain the value 5

If F9 contains the value 5, then F3 cannot contain the value 5

Because the cell F9 cannot contain other values, and the results are the same, we can conclude that F3 cannot contain the value 5.

Each assertion is proved by a different chain of simple rules. The chains can be dynamic, which means that the conclusions of multiple sub-chains must be combined in some cases.

The details of each chain are given below. Use the view selector below the grid to switch between the graphical illustrations of the different chains.

Chain 1: If F9 contains the value 3, then F3 cannot contain the value 5 (View 1): (1) If F9 contains the value 3, then D9 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the block) (2) If D9 does not contain the value 3, then D4 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the column) (3) If D4 contains the value 3, then G4 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the row) (4) If G4 does not contain the value 3, then G4 must contain the value 2 (only remaining possible value in the cell) (5) If G4 contains the value 2, then H5 cannot contain the value 2 (the value can occur only once in the block) (6) If H5 does not contain the value 2, then A5 must contain the value 2 (only remaining possible position in the row) (7) If A5 contains the value 2, then A5 cannot contain the value 3 (the cell can contain only one value) (8) If D4 contains the value 3 (2), then A4 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the row) (9) If D4 contains the value 3 (2), then B4 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the row) (10) If B4 does not contain the value 3, A4 does not contain the value 3 (8) and A5 does not contain the value 3 (7), then A6 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the block) (11) If A6 contains the value 3, then G6 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the row) (12) If G4 does not contain the value 3 (3) and G6 does not contain the value 3, then G3 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the column) (13) If G3 contains the value 3, then I2 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the block) (14) If A6 contains the value 3 (10), then A2 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the column) (15) If G3 contains the value 3 (12), then H2 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the block) (16) If H2 does not contain the value 3, A2 does not contain the value 3 (14) and I2 does not contain the value 3 (13), then B2 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the row) (17) If B2 contains the value 3, then B2 cannot contain the value 5 (the cell can contain only one value) (18) If G4 contains the value 2 (4), then G1 cannot contain the value 2 (the value can occur only once in the column) (19) If G1 does not contain the value 2, then G1 must contain the value 5 (only remaining possible value in the cell) (20) If G1 contains the value 5, then B1 cannot contain the value 5 (the value can occur only once in the row) (21) If B1 does not contain the value 5 and B2 does not contain the value 5 (17), then B3 must contain the value 5 (only remaining possible position in the block) (22) If B3 contains the value 5, then F3 cannot contain the value 5 (the value can occur only once in the row) Chain 2: If F9 contains the value 5, then F3 cannot contain the value 5 (View 2): (1) If F9 contains the value 5, then F3 cannot contain the value 5 (the value can occur only once in the column)In short, these puzzles require brute force to solve. No human would have the patience to solve them.

puzzles6_forum_hardest_1106

A quick mention of the puzzles4 and puzzles5 dataset, they have largely the same backstory of puzzles6: collections of the hardest sudoku puzzles generated by the forum. However these sets contained more puzzles, and the difficulty was more “dilute”. However they were still crazy hard, and were strictly harder than even the puzzles in the previous dataset.

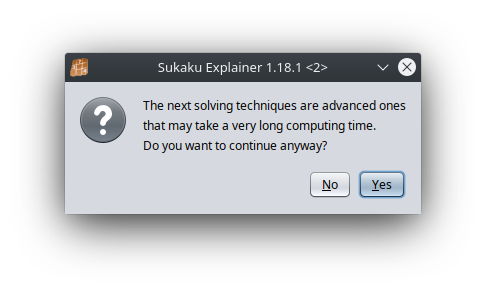

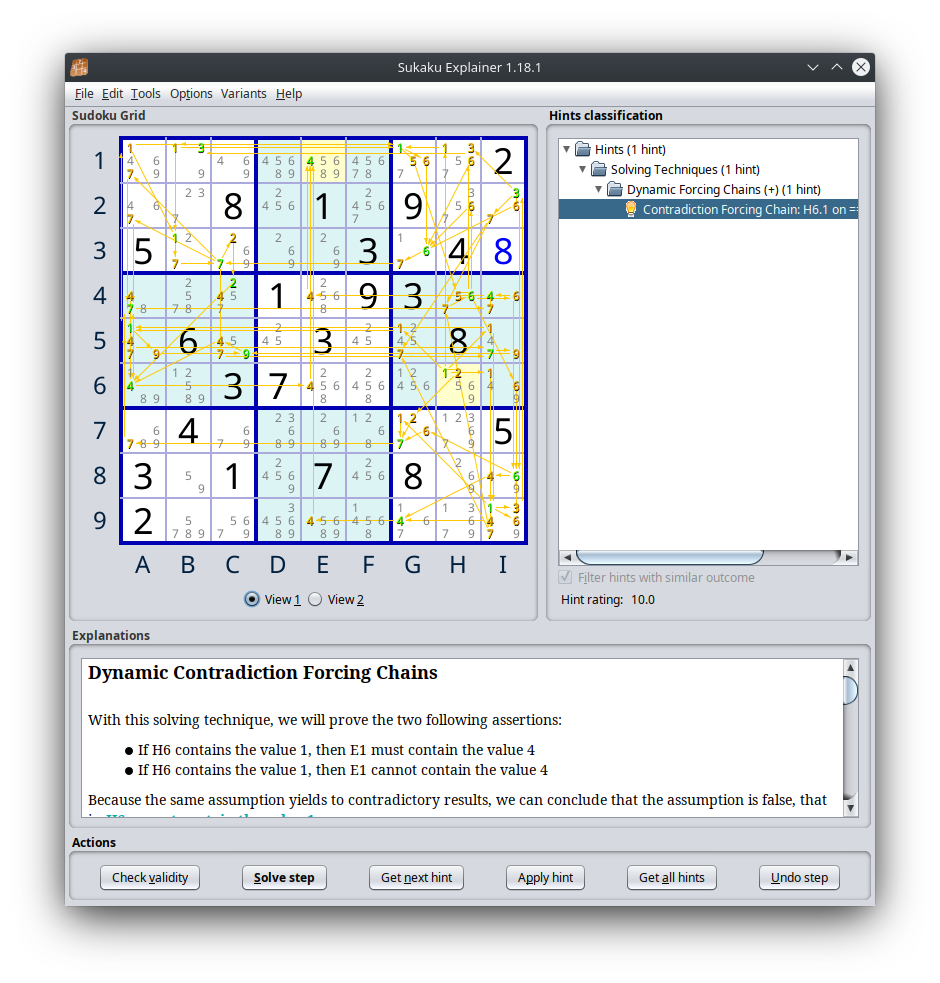

We skip ahead to puzzles6, a collection of the hardest puzzles amongst the hardest puzzles. Plugging them into sukaku explainer, we are greeted with a particularly forboding message.

This happens a couple of times, and each time out pops a very cooked deduction chain. Here is an impressively cooked deduction.

Click to show the full deduction

Dynamic Contradiction Forcing Chains

With this solving technique, we will prove the two following assertions:

If H6 contains the value 1, then E1 must contain the value 4

If H6 contains the value 1, then E1 cannot contain the value 4

Because the same assumption yields to contradictory results, we can conclude that the assumption is false, that is, H6 cannot contain the value 1.

Each assertion is proved by a different chain of simple rules. The chains can be dynamic, which means that the conclusions of multiple sub-chains must be combined in some cases.

The details of each chain are given below. Use the view selector below the grid to switch between the graphical illustrations of the two different chains.

Chain 1: If H6 contains the value 1, then E1 cannot contain the value 4 (View 1): (1) If H6 contains the value 1, then I6 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (2) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then I5 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (3) If I5 does not contain the value 1 and I6 does not contain the value 1 (1), then I9 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the column) (4) If I9 contains the value 1, then I9 cannot contain the value 3 (the cell can contain only one value) (5) If I9 does not contain the value 3, then I2 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the column) (6) If I2 contains the value 3, then I2 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (7) If I9 contains the value 1 (3), then I9 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (8) If I9 does not contain the value 7 and I2 does not contain the value 7 (6), then H4 cannot contain the value 7 (Claiming: Cells I4,I5: 7 in column and block) (9) If I2 contains the value 3 (5), then H1 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the block) (10) If H1 does not contain the value 3, then B1 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the row) (11) If B1 contains the value 3, then B1 cannot contain the value 1 (the cell can contain only one value) (12) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then G5 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (13) If G5 does not contain the value 1 and I5 does not contain the value 1 (2), then A5 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the row) (14) If A5 contains the value 1, then A1 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the column) (15) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then H1 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the column) (16) If H1 does not contain the value 1, A1 does not contain the value 1 (14) and B1 does not contain the value 1 (11), then G1 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the row) (17) If G1 contains the value 1, then G1 cannot contain the value 5 (the cell can contain only one value) (18) If G1 does not contain the value 5, then H4 cannot contain the value 5 (Pointing: Cells H1,H2: 5 in block and column) (19) If H4 does not contain the value 5 and H4 does not contain the value 7 (8), then H4 must contain the value 6 (only remaining possible value in the cell) (20) If H4 contains the value 6, then H2 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the column) (21) If G1 contains the value 1 (16), then G1 cannot contain the value 6 (the cell can contain only one value) (22) If H4 contains the value 6 (19), then H1 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the column) (23) If I2 contains the value 3 (5), then I2 cannot contain the value 6 (the cell can contain only one value) (24) If I2 does not contain the value 6, H1 does not contain the value 6 (22), G1 does not contain the value 6 (21) and H2 does not contain the value 6 (20), then G3 must contain the value 6 (only remaining possible position in the block) (25) If G3 contains the value 6, then G3 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (26) If A1 does not contain the value 1 (14) and B1 does not contain the value 1 (11), then B3 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the block) (27) If B3 contains the value 1, then B3 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (28) If B3 does not contain the value 7 and G3 does not contain the value 7 (25), then C3 must contain the value 7 (only remaining possible position in the row) (29) If C3 contains the value 7, then C5 cannot contain the value 7 (the value can occur only once in the column) (30) If A5 contains the value 1 (13), then A5 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (31) If I9 does not contain the value 7 (7) and I2 does not contain the value 7 (6), then G5 cannot contain the value 7 (Claiming: Cells I4,I5: 7 in column and block) (32) If G5 does not contain the value 7, A5 does not contain the value 7 (30) and C5 does not contain the value 7 (29), then I5 must contain the value 7 (only remaining possible position in the row) (33) If I5 contains the value 7, then I5 cannot contain the value 9 (the cell can contain only one value) (34) If A5 contains the value 1 (13), then A5 cannot contain the value 9 (the cell can contain only one value) (35) If A5 does not contain the value 9 and I5 does not contain the value 9 (33), then C5 must contain the value 9 (only remaining possible position in the row) (36) If C5 contains the value 9, then C5 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (37) If C3 contains the value 7 (28), then A2 cannot contain the value 7 (the value can occur only once in the block) (38) If C3 contains the value 7 (28), then A1 cannot contain the value 7 (the value can occur only once in the block) (39) If H4 contains the value 6 (19), then I6 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the block) (40) If H4 contains the value 6 (19), then I4 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the block) (41) If I9 contains the value 1 (3), then I9 cannot contain the value 6 (the cell can contain only one value) (42) If I9 does not contain the value 6, I4 does not contain the value 6 (40), I2 does not contain the value 6 (23) and I6 does not contain the value 6 (39), then I8 must contain the value 6 (only remaining possible position in the column) (43) If I8 contains the value 6, then G7 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the block) (44) If I9 contains the value 1 (3), then G7 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (45) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then H6 cannot contain the value 2 (the cell can contain only one value) (46) If H6 does not contain the value 2, then G7 cannot contain the value 2 (Pointing: Cells G5,G6: 2 in block and column) (47) If G7 does not contain the value 2, G7 does not contain the value 1 (44) and G7 does not contain the value 6 (43), then G7 must contain the value 7 (only remaining possible value in the cell) (48) If G7 contains the value 7, then A7 cannot contain the value 7 (the value can occur only once in the row) (49) If A7 does not contain the value 7, A5 does not contain the value 7 (30), A1 does not contain the value 7 (38) and A2 does not contain the value 7 (37), then A4 must contain the value 7 (only remaining possible position in the column) (50) If A4 contains the value 7, then A4 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (51) If C3 contains the value 7 (28), then C3 cannot contain the value 2 (the cell can contain only one value) (52) If C3 does not contain the value 2, then C4 must contain the value 2 (only remaining possible position in the column) (53) If C4 contains the value 2, then C4 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (54) If A5 contains the value 1 (13), then A5 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (55) If A5 does not contain the value 4, C4 does not contain the value 4 (53), A4 does not contain the value 4 (50) and C5 does not contain the value 4 (36), then A6 must contain the value 4 (only remaining possible position in the block) (56) If A6 contains the value 4, then E6 cannot contain the value 4 (the value can occur only once in the row) (57) If A4 contains the value 7 (49), then I4 cannot contain the value 7 (the value can occur only once in the row) (58) If I4 does not contain the value 6 (40) and I4 does not contain the value 7, then I4 must contain the value 4 (only remaining possible value in the cell) (59) If I4 contains the value 4, then E4 cannot contain the value 4 (the value can occur only once in the row) (60) If I8 contains the value 6 (42), then I8 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (61) If I9 contains the value 1 (3), then I9 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (62) If I9 does not contain the value 4 and I8 does not contain the value 4 (60), then G9 must contain the value 4 (only remaining possible position in the block) (63) If G9 contains the value 4, then E9 cannot contain the value 4 (the value can occur only once in the row) (64) If E9 does not contain the value 4, E4 does not contain the value 4 (59) and E6 does not contain the value 4 (56), then E1 must contain the value 4 (only remaining possible position in the column)

Chain 2: If E1 must contain the value 4, then E1 cannot contain the value 4 (View 2): (1) If H6 contains the value 1, then I6 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (2) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then I5 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (3) If I5 does not contain the value 1 and I6 does not contain the value 1 (1), then I9 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the column) (4) If I9 contains the value 1, then I9 cannot contain the value 3 (the cell can contain only one value) (5) If I9 does not contain the value 3, then I2 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the column) (6) If I2 contains the value 3, then I2 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (7) If I9 contains the value 1 (3), then I9 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (8) If I9 does not contain the value 7 and I2 does not contain the value 7 (6), then H4 cannot contain the value 7 (Claiming: Cells I4,I5: 7 in column and block) (9) If I2 contains the value 3 (5), then H1 cannot contain the value 3 (the value can occur only once in the block) (10) If H1 does not contain the value 3, then B1 must contain the value 3 (only remaining possible position in the row) (11) If B1 contains the value 3, then B1 cannot contain the value 1 (the cell can contain only one value) (12) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then G5 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the block) (13) If G5 does not contain the value 1 and I5 does not contain the value 1 (2), then A5 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the row) (14) If A5 contains the value 1, then A1 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the column) (15) If H6 contains the value 1 (initial assumption), then H1 cannot contain the value 1 (the value can occur only once in the column) (16) If H1 does not contain the value 1, A1 does not contain the value 1 (14) and B1 does not contain the value 1 (11), then G1 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the row) (17) If G1 contains the value 1, then G1 cannot contain the value 5 (the cell can contain only one value) (18) If G1 does not contain the value 5, then H4 cannot contain the value 5 (Pointing: Cells H1,H2: 5 in block and column) (19) If H4 does not contain the value 5 and H4 does not contain the value 7 (8), then H4 must contain the value 6 (only remaining possible value in the cell) (20) If H4 contains the value 6, then H2 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the column) (21) If G1 contains the value 1 (16), then G1 cannot contain the value 6 (the cell can contain only one value) (22) If H4 contains the value 6 (19), then H1 cannot contain the value 6 (the value can occur only once in the column) (23) If I2 contains the value 3 (5), then I2 cannot contain the value 6 (the cell can contain only one value) (24) If I2 does not contain the value 6, H1 does not contain the value 6 (22), G1 does not contain the value 6 (21) and H2 does not contain the value 6 (20), then G3 must contain the value 6 (only remaining possible position in the block) (25) If G3 contains the value 6, then G3 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (26) If A1 does not contain the value 1 (14) and B1 does not contain the value 1 (11), then B3 must contain the value 1 (only remaining possible position in the block) (27) If B3 contains the value 1, then B3 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (28) If B3 does not contain the value 7 and G3 does not contain the value 7 (25), then C3 must contain the value 7 (only remaining possible position in the row) (29) If C3 contains the value 7, then C5 cannot contain the value 7 (the value can occur only once in the column) (30) If A5 contains the value 1 (13), then A5 cannot contain the value 7 (the cell can contain only one value) (31) If I9 does not contain the value 7 (7) and I2 does not contain the value 7 (6), then G5 cannot contain the value 7 (Claiming: Cells I4,I5: 7 in column and block) (32) If G5 does not contain the value 7, A5 does not contain the value 7 (30) and C5 does not contain the value 7 (29), then I5 must contain the value 7 (only remaining possible position in the row) (33) If I5 contains the value 7, then I5 cannot contain the value 9 (the cell can contain only one value) (34) If A5 contains the value 1 (13), then A5 cannot contain the value 9 (the cell can contain only one value) (35) If A5 does not contain the value 9 and I5 does not contain the value 9 (33), then C5 must contain the value 9 (only remaining possible position in the row) (36) If C5 contains the value 9, then C5 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (37) If C3 contains the value 7 (28), then C3 cannot contain the value 2 (the cell can contain only one value) (38) If C3 does not contain the value 2, then C4 must contain the value 2 (only remaining possible position in the column) (39) If C4 contains the value 2, then C4 cannot contain the value 4 (the cell can contain only one value) (40) If C4 does not contain the value 4 and C5 does not contain the value 4 (36), then C1 must contain the value 4 (only remaining possible position in the column) (41) If C1 contains the value 4, then E1 cannot contain the value 4 (the value can occur only once in the row)